The word “criticism,” in the context of translating the Bible and “what a verse means,” could easily be mistaken for its more popular meaning of belligerence, denigration, combativeness, slander, even vilification. “Those First Church people couldn’t translate a verse if it hit them in the mouth!” “Oh Yeah! You Second Church people …”

Textual Criticism Is Good Criticism

But the “criticism” in textual criticism is the good kind—interpretation, analysis, elucidation, evaluation, assessment, etc.—a detailed and careful approach to the original biblical texts.

The details behind multiple Bible versions is complex, but so worth becoming familiar with as you seek to study the Bible more effectively. So if it seems Bible Versions 101 veered off the path of discovering what’s up with the KJV, NLT, NRSV, ESV, NKJV, NIV, etc. etc., hold on tight while reading Bible Versions 102, because it may seem like a never ending rabbit trail.

The Importance of Textual Criticism For Effective Bible Study

You did catch the term “may seem,” right? Because the subject of this post is quite important in the Science of Translation. It is important for Bible translators, and it is important for you too. Understanding textual criticism is important because it will:

- Explain all the markings and footnotes found in your Bible(s)

- Offer valuable insight when doing Word Studies in the original language

The Bible Versions Series So Far

Bible Versions 101: Why Are There So Many Bible Versions? discusses the difference between translation and interpretation.

- Translation – translating the words of one language to the words of another language

- Interpretation – explaining the meaning of the words translated; if someone speaks to you in sign language, it is probable that you would need an interpreter to explain the meaning of the signs.

Bible Versions 102 discusses Textual Criticism, which has to do with the original text. The “from” version, i.e. translating from Greek to English, from Hebrew to German, etc.

Textual Criticism is not this kind of criticism, it is good criticism, as in interpretation, analysis, elucidation, evaluation, and assessment.

The Task of Translation

You may recall that anytime a translator takes on the task of translation, two types of choices must be made:

- Textual Choices – the actual wording of the original text

- Linguistic Choices – a theory of translation

(Linguistics = the study of language and of the way languages work)

In the Bible Versions Series, this post discusses the textual choices.

Textual Choices

Textual choices that must be made by the translator involve choices related to the original text of the Bible. The following statement may seem obvious, though the story of the two elderly men and the Chinese missionary (in Bible Versions 101) prove that it is not—

translations begin with the original text.

Original Text

The translator must make sure the Hebrew or Greek manuscripts (MSS) being used are reliable, that is, as close as possible to what the Biblical author wrote or dictated.

The printing press was not invented until 1444 A.D., so this means the books, letters, etc. of the Bible had to be copied by hand—over and over for hundreds of years. And among the multiple copies, variants exist.

Textual Criticism is the discipline devoted to the study of textual variants, i.e. differences between the multiple copies of manuscripts. But in the end, the translator, who is adept in this discipline, decides which variant most likely represents the original text.

[A not so quick aside. ***The idea of MSS’ variants should cause no alarm. With an amazing degree of accuracy, the entire Bible has been faithfully passed down from one generation to the next, all the way down to us today. Variants are discussed briefly since understanding them will increase your understanding of Scripture and the Bible you hold in your hands.

In your studies, you will come across discussions of variants, and to be sure, they are noted in most Bibles. Just look between John 7 and 8 for an example. In addition, variants are discussed in commentaries, sometimes to the extent of discussing the variant more than the actual meaning of the text! The point is, you will come across them in your study and research.

So consider this—God’s Word has survived wars, fires, exiles, false teachers, robbers, earthquakes, persecution, apostasy, vassal dependence, and more, over 1000’s of years. It is a testimony to God and His Word to humanity that we have 66 books by different authors written at different times, and all 66 have a unified message! Glory to God! We can trust that God, in His great faithfulness, has given us Scripture as is, and no variant is so great as to make a Christian doubt any “jot or tittle” (Matt. 5:18).]

Textual Criticism

Textual Criticism is “the science that attempts to discover the original texts of ancient documents.”

From this definition it is clear that textual criticism is not a science dealing only with study of the Bible. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Iliad, Vedas, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Julius Caesar Gaelic Wars, The Canterbury Tales, all the works of Shakespeare—to name only a very few—are all scrutinized by textual criticism.

As you can imagine, the field is massive and complex. It would be worthwhile to read a couple of articles on the subject, even though you will probably never discuss “textual criticism” in a class, speech, or sermon—you do want people to stay awake, right?

Seriously, it helps to know something about it so that you can make better sense of the notes in your Bible, i.e. “The earliest manuscripts do not include…”, i.e. John 7:53-8:11 ; Mark 16:9-20; or “Some manuscripts add…”. In addition, doing Greek and Hebrew word studies may require that you research the text critical aspects of a verse.

Two Types of Evidence

In attempting to discover the original texts of ancient documents, i.e. in doing text critical tasks, two types of evidence are used in making decisions about the text:

- External

- Internal

External Evidence

External evidence refers to the physical documents. Physical evidence has to do with the quality and age of the MSS that support a given variant. Each manuscript has a referential name, and each falls in a general category.

OT:

- Masoretic Text (MT) – based on a very careful copying method by the Masoretes

- Septuagint (LXX) – Greek translation of the Hebrew text

- Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) – dated before Christianity and supports the reliability of the MT

NT:

- Greek MSS – mostly from Egypt, earliest written on papyrus (survives well in dry sands), and later MSS written on parchment;

- Early Versions – Latin, Syriac, Coptic MSS; evidence for a particular reading in the place and time of its origin

- Early Church Fathers – NT quoted extensively in their writings

Internal Evidence

Internal evidence refers to the text itself, i.e. the content of the MSS. This evidence relates to the copyists (those who copied the MSS) and authors (Moses, Paul, etc.).

- Copyists – habits and mistakes of copyists tend to be the same, for example,

- a letter or word copied incorrectly

- “correcting” a text for theological purposes, etc.

- when one variant can provide an explanation of how the others came about, this is good internal evidence that it is the original

- Authors – knowing the author’s style and word choice

The external evidence plus the internal evidence combine to give a high degree of certainty as to which reading is the original text.

A Textual Criticism Sample Paper

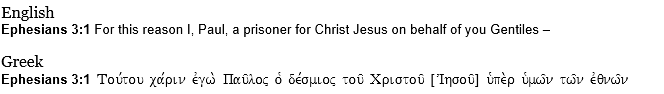

My NT Greek Exegesis professor, Dr. Frank Thielman, gave the class a textual criticism assignment on Ephesian 3:1.

The brackets in the Greek text contain the word “Jesus.” So the text critical question is did Paul say “a prisoner of Christ Jesus” or did he say “a prisoner of Christ”?Here is a copy of my Ephesians 3.1 Textual Criticism paper from early seminary days of Fall 2005, so please be kind with any criticism, pun intended. It is a good example of the detail involved in doing even this relatively simple text critical task, along with the struggles of doing this for the first time.

Example of Doing A Text Critical Analysis

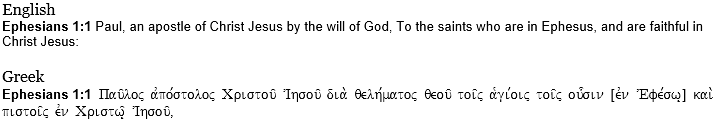

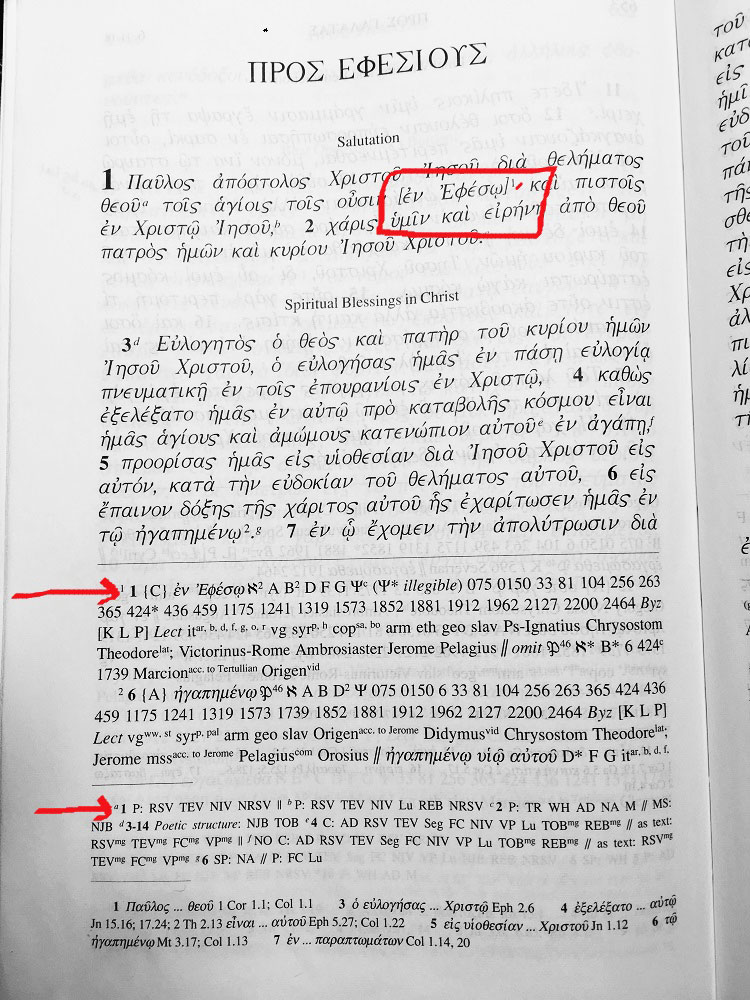

As an illustration, let’s briefly work through a text critical example using Ephesians 1:1. This will demonstrate the multiple steps involved in doing textual criticism. (Since the analysis from Bruce Metzger’s Textual Commentary on the NT is included below, this example will only comment briefly on external evidence.)

The Text Critical Question In Ephesians 1:1

The brackets in the Greek text above contain the words “in Ephesus.” The question is did Paul say “to the saints who are in Ephesus and are faithful in Christ Jesus” or did he say “to the saints who are faithful in Christ Jesus”?

1. Evaluation of External Evidence

External evidence–the phrase “in Ephesus” is not included in 5 important witnesses, i.e. early and good quality MSS, but it is included in all other witnesses with the exception of a couple of church fathers.

Also, the letter has been traditionally known as the letter to the Ephesians.

Evaluation of External evidence – external evidence is neutral

2. Evaluation of Internal Evidence

Internal evidence includes style of the author and copyists.

a. style of the author– Following proper Hellenistic letter writing conventions, Paul normally includes the church or individual to whom he is writing; all of his letters address someone specifically, so there is a great probability that Ephesians would do this as well.

- Romans 1:7 To all those in Rome who are loved by God and called to be saints:

- 1 Corinthians 1:2 To the church of God that is in Corinth,

- 2 Corinthians 1:1 Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, and Timothy our brother, To the church of God that is at Corinth

- Galatians 1:2 and all the brothers who are with me, To the churches of Galatia:

- Philippians 1:1 Paul and Timothy, servants of Christ Jesus, To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are at Philippi,

- Colossians 1:2 To the saints and faithful brothers in Christ at Colossae:

- 1 Thessalonians 1:1 Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy, To the church of the Thessalonians

- 2 Thessalonians 1:1 Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy, To the church of the Thessalonians

- 1 Timothy 1:2 To Timothy,

- 2 Timothy 1:2 To Timothy, my beloved child:

- Titus 1:4 To Titus, my true child in a common faith:

- Philemon 1:1 Paul, a prisoner for Christ Jesus, and Timothy our brother, To Philemon our beloved fellow worked

b. copyists – how can the addition, or removal, of the variant be explained?

Think about Paul’s letters. Most address specific problems in the church to which he is writing. That is, all except for Ephesians. Relatively speaking, it is somewhat generic.

So it is plausible to assume that a copyist—in the early days of the church—may have removed “in Ephesus” so that the letter would be addressed to all Christians of that time, even adding the word “also”.

No copyist would have removed a specification such as “to the church at Corinth” (1 Cor. 1:2), since the problems mentioned in 1 and 2 Corinthians are very specific to that church. Also, 1 and 2 Corinthians mentions the names of multiple church members throughout each letter, whereas Ephesians does not.

So it is likely that the copyist (with the very best of intentions) changed the original text from:

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, To the saints who are in Ephesus, and are faithful in Christ Jesus:

To:

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, To the saints who are also faithful in Christ Jesus.

Evaluation – strong internal evidence, matches Paul’s style and the copyist variant can be explained

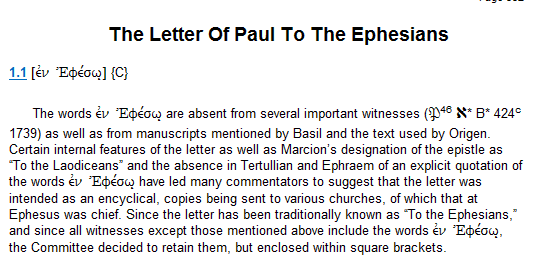

3. Textual Commentary Analysis of Ephesians 1:1

Bruce Metzger’s Textual Commentary on the NT contains notes related to the variants in the Greek NT. Here is the entry for Ephesians 1:1 –

Note the {C} above. This designation communicates the committee’s certainty factor about the textual choice. The values used are:- A = certain

- B = almost certain

- C = difficulty deciding which variant to put in place

- D = difficulty arriving at any decision (very rare)

4. Final Evaluation of the Example

So from our sample analysis, you can understand why the committee gave this a {C}.

External evidence—variant missing from some important MSS;

Internal evidence—fits Paul’s normal writing style and easily explained from the viewpoint of a copyist in the early church.

Combining the external and internal renders the C certainty factor—”difficultly deciding which variant to put in place.”

The internal evidence is great, but 5 of the most important MSS do not have the variant.

What do you think?

Is There a List of All the Variants?

Each Bible version has notes about textual variants which may be sufficient for your study. Here are a couple of examples:

ESV Ephesians 1:1 has this marginal note:

“Some manuscripts saints who are also faithful (omitting in Ephesus)”

ESV John 7:52 They replied, “Are you from Galilee too? Search and see that no prophet arises from Galilee.”

THE EARLIEST MANUSCRIPTS DO NOT INCLUDE JOHN 7:53-8:11

Otherwise, the textual notes, i.e. apparatus, can be found in the Greek NT and the Hebrew OT. The apparatus gives a complete list of variants and MSS evidence.

Ephesians 1:1 Example

This is the first page of Ephesians from The Greek New Testament (4th Revised Ed.). Pros Ephesious = To The Ephesians. The variant en Epheso can be seen in the red rectangle.

The superscript 1 is by the phrase in question. Find the 1 at the bottom of the page.

It lists all manuscripts where the variant is found, as well as where it is not.

The second red arrow shows how the variant is translated in multiple Bible versions. (lists of footnote abbreviations are included in the Greek NT)

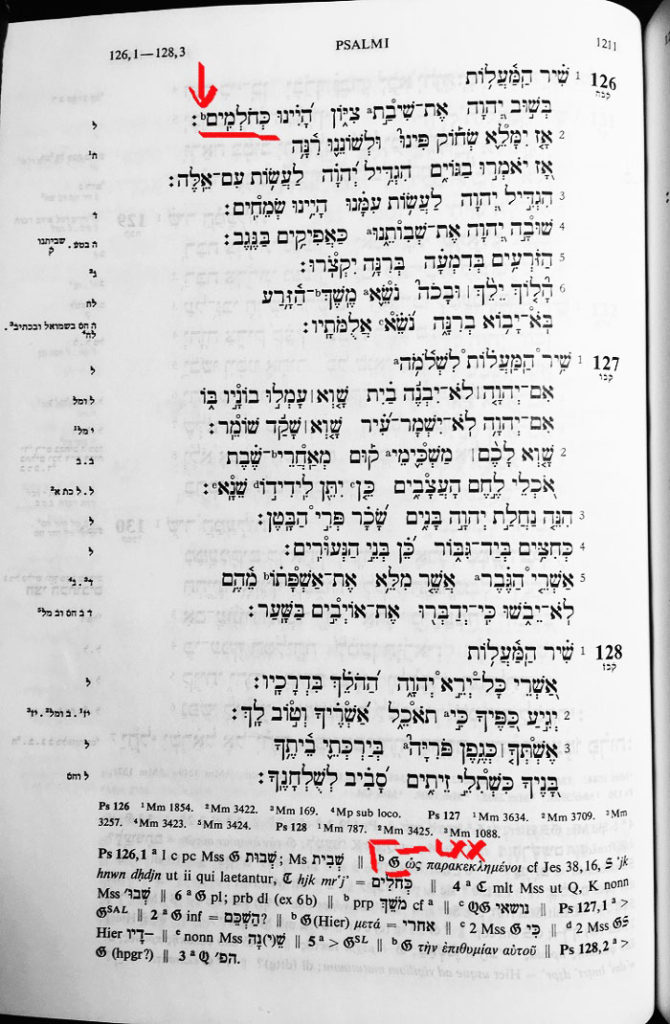

Psalm 126:1 Example

Here is an example of a variant from the Hebrew Bible (Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, BHS). The variant is in Psalm 126:1. The question is does it say “When the LORD restored the fortunes of Zion, we were like those who dream” or “…like those who are comforted”?

The superscript ‘b‘ is by the verb in question. Find the ‘b‘ in the footnotes and it will list the variant readings along with MSS notations.

For Psalm 126:1 a variant reading exists in the Septuagint (LXX), denoted by a large Script (or Black-letter) ‘G‘ as well as a few other MSS.

A note to refer to Isaiah 38:16 (Jes 38,16) is included. (Lists of all footnote abbreviations are included in the Hebrew Bible.)

The outer margin markings are known as the Masorah and are various notes inserted by the Masoretes, the Hebrew Bible copyists; more to come on this fascinating subject.

Textual Criticism, Like Most Sciences, Is Not Exact

In summary, some variants may have equally good internal and external evidence. So translators may try to determine the original text based on theological context, as well as the historical context of copies. Even this may not provide any degree of certainty.

Most translations are done by committees. In cases like these, it will be decided on committee vote, of course with the minority rendering noted in the margins. Whatever is decided will be well documented.

So What?

Here’s what. Here is the point of Textual Criticism in the context of Bible Versions.

Because these variants exist,

and because textual criticism is not an exact science,

and some differences can’t be explained easily—this is one reason for differences between translations. This is also why translators are also interpreters.

I confess Textual Criticism is not the most exhilarating topic in Biblical study. But it is a topic within Biblical Study nonetheless. As a faithful Bible teacher, preacher, writer, blogger, student, parent, Christian, etc., you need to be aware of textual criticism, aware of what it does, how the evidence is analyzed, etc.

If you use a good Bible software, such as BibleWorks™, it will have text critical resources that can be accessed with the click of a button. Otherwise, here are some very good print/digital references:

- Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

- David Alan Black, New Testament Textual Criticism: A Concise Guide, Baker Academic, 1994.

- Ellis R. Brotzman, Old Testament Textual Criticism: A Practical Introduction, Baker Academic 1993.

- Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, 3rd ed., Fortress Press, 2011.

- Page H. Kelly, Timothy G. Crawford, and David S. Mynatt, The Masorah of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia: Introduction and Annotated Glossary, Wm. B. Eerdsmans Publishing, 1998.

These include a short history of textual criticism, methodologies, and lists and abbreviations of MSS.

The Bible Versions Series Coming Up

After translation and interpretation (101) and textual criticism (102), Bible Versions 103 discusses the translation theory used in the various Bible versions. You can check out the remainder of RDRD Bible Study’s 4-part series on Bible Versions here:

Until next time –

The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Ghost, be with you all. Amen. <The second epistle to the Corinthians was written from Philippi, a city of Macedonia, by Titus and Lucas.> 2 Corinthians 13:14, KJV

P.S. I’m using the KJV version of 2 Corinthians 13:14 for this post instead of the typical ESV “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all” (2 Cor. 13:14).

Call it a teaching moment.

As you can see, the KJV has additional text marked off by the “<>” that is not included in modern versions, not even the NKJV. The KJV was translated from the Byzantine text type which 1) represents late MSS witnesses, and 2) has a great deal of textual variants, relatively speaking, because of what the “translators” were trying to accomplish (which can be read about in resources on textual criticism of the Bible, i.e. optional homework).

Homework (optional, but you will be sooo glad you did it):

- What is the Byzantine text type?

- Why does it have a greater number of variant readings than the Alexandrian or Latin text types?

Post your answers in the comments. We learn the most in community.