Looking back over the vast expanse of Christian History, without a doubt, the largest sea changes have occurred when men and women exercised an unwavering belief in the primacy and authority of Holy Scripture. Fundamental to this doctrine of Scripture is faith in who God is and what God does. And concomitantly, that Scripture is the Word of God.

John Wycliffe (1330-1384) is one such wave maker in Christian history. Plenty of books and articles exist on the life and work of Wycliffe. A few are referenced in the resources section at the end of this post. So why another?

St. Bede once said: “Unfurl the sails, and let God steer us where He will.” This article seeks to illustrate how Wycliffe’s life and ministry were carried along by the unfurled sails of a relentless belief that Scripture is paramount to Christian Life. In the treacherous currents of 14th century Europe, his sails caught the wind that blows where it wishes, and God steered him along, changing the course of Christianity forever.

Wycliffe’s Greatest Contribution

In an article detailing Wycliffe’s contributions as a great reformer and theologian, David B. Calhoun, a professor of Church History writes:

Wycliffe’s greatest contribution to church history was his elevation of the Bible to its supreme place and his insistence that it be made available to all Christians in their own language. In his book, The Truth of Holy Scripture, Wycliffe declared that Scripture was divinely inspired in every part and that it was the source of doctrine and the standard of life for all people, from peasants to kings and popes.

By the fourteenth century, a few portions of the Bible had been translated into Old English, but there was no version in the everyday language of most of the English people. John Wycliffe inspired and organized the work of providing such a Bible. There were two “Wycliffite” translations. The second and far superior was by John Purvey, an Oxford disciple of Wycliffe. Completed about 1395, a decade after Wycliffe’s death from natural causes on New Year’s Eve 1384, it was a translation of a translation, the Latin Vulgate translated into English. Purvey used the dialect of London, like Chaucer in The Canterbury Tales, making Middle English the dominant form of the language. Wycliffe’s vision and Purvey’s Bible prepared the way for the work of William Tyndale and the translators of the Geneva Bible in the sixteenth century and the King James Version of 1611, as well as the many English translations that have followed.

So why start out with the end? It’s easy enough to read a quote like the above, tuck it away in your mind, and think “oh, what a great and godly man.” But what kind of life does a person have and live, that can be summed up by such extraordinary words? And ultimately, how might his faith influence our life and work for Jesus Christ?

John Wycliffe embodied Sola scriptura before Sola scriptura was cool.

150 Years After Wycliffe

Note the similarities in theology between this Luther quote and this from Wycliffe: “Christians should rely on the Bible rather than on the teachings of popes and clerics.”

The key to fully appreciating the extremely radical nature of Wycliffe’s life and work, is to look briefly at the Protestant Reformation.

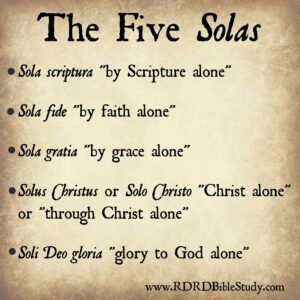

Sola Scriptura, a Latin phrase meaning “by Scripture alone” is one of five solas considered by most Protestants to be the theological pillars of the Reformation (1517-1648). The term rose to prominence from the writings and teachings of Martin Luther (Germany, 1483-1546): sola fide, by faith alone, and sola gratia, by grace alone, both emanating from sola Scriptura.

Most people are familiar with Martin Luther’s 95 theses that launched the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. Likewise, his theology, considered blasphemous at the time—150 years after Wycliffe—that challenged the authority and office of the Pope. In opposition to contemporary belief, Luther taught that the Bible is the only source of divinely revealed knowledge from God.

Radical Nature of Wycliffe’s Life and Work

Approximately 150 years prior to Luther in Germany, John Wycliffe taught many of the same principles in England. Interest in Wycliffe’s theology came about because of its similarity to the Protestant Reformers, especially in the primacy and authority of Scripture for Christian thought and life. This is why he is often called “The Morning Star of the Reformation.”

Why “Radical”?

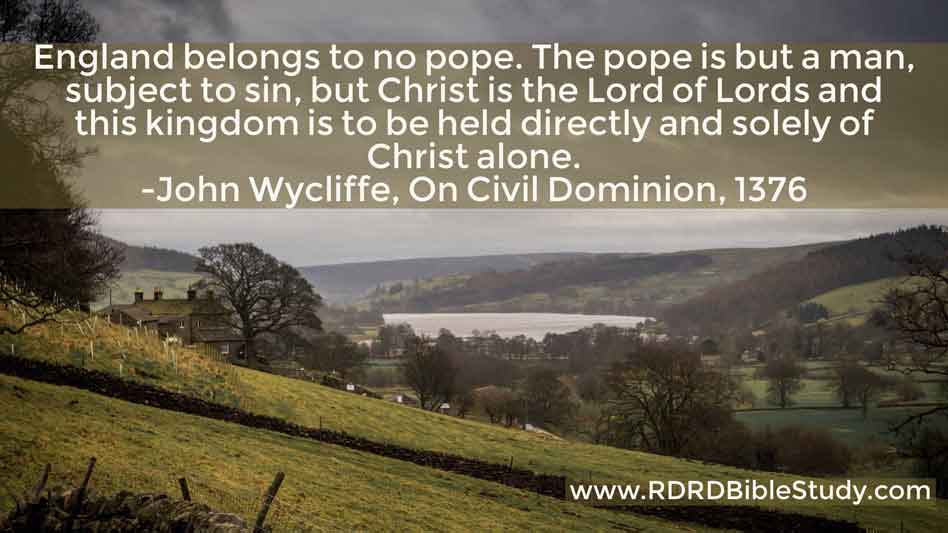

The “radical” belief in the primacy and authority of Scripture stood in direct opposition to papal claims of the same primacy and authority. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that the authority attributed to papal primacy is the “full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise unhindered.” Moreover, prior to the Reformation, the papal office and clergy also possessed secular authority.Though the history of the papacy is long and debated, during Wycliffe’s time it was largely not questioned. But as the familiar saying goes “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” so rumblings concerning the office of pope had been escalating since the beginning of the 1300’s.

Earlier conflict had led to the establishment of an Avignon Papacy (1309-1376) during which 7 successive popes resided, as opposed to Rome (the successor to Peter theory squashed). When the church attempted to resolve the conflict, it led to The Western Schism (1378-1417), aka The Papal Schism, where 3 men simultaneously claimed to be pope. Wycliffe deemed this a positive turn, even saying that Christ “hath begun already to help us graciously, in that he hath cloven the head of Antichrist, and made the two parts fight against each other.”

John Wycliffe (1329-1384)

So… long, long ago, in a world before the King James Bible (which is not the original language of the Bible) lived John Wycliffe, the namesake of the Wycliffe Bible—the first complete English Bible.

The Five Solas of the Protestant Reformation

In this pre-Protestant, pre-Evangelical environment, which is difficult for anyone to imagine, Wycliffe’s courageous undertakings and prominence as an Oxford professor and Catholic priest, served as the inspiration for this principal milestone in Christian history.

3 Phases of Wycliffe’s Life

Historians divide Wycliffe’s life into 3 phases:

- Studied at Oxford beginning approx. 1345; by 1360, master of Balliol College, and by 1370, Oxford’s leading theologian and philosopher

- Entered the service of the Crown in the early 1370’s

- Returned to his studies at Oxford in 1378

Early Factors in the Development of Wycliffe’s Theology

Black Plague

Not long after Wycliffe went to Oxford, the Black Plague, aka Black Death, killed a third of the population of England. The plague claimed the lives of an estimated 75 to 200 million people in Eurasia and peaked in Europe during 1346–1353. According to an early editor and translator of Wycliffe’s works, Robert Vaughn (1845), the experience greatly affected Wycliffe giving him “Very gloomy views in regard to the condition and prospects of the human race.” Because the church was an overarching part of society, Wycliffe was greatly affected by the Black Death and began to question the spiritual basis of the church. The magnitude of the plague is difficult to imagine. Thomas Murray gives an eerie glance:

It began its devastating career there in 1348; ere long it reached the metropolis; and though it did not entirely disappear for eleven years, its virulence was confined to a few months; during which short time, not fewer than half of the whole inhabitants of London are calculated to have perished. The infected generally died within a few hours: the strongest did not survive the third day. It extended its virulence to the lower animals also: so that the labours of husbandry were suspended. The courts of justice were closed; business of every kind was abandoned; death, or mourning for the dead, and despair shook the fabric of society to its very centre, and threatened the country with universal desolation.

Archbishop of Canterbury Treatise On Redeeming Grace and Original Sin

Wycliffe was both doctrinal and polemical. Intertwined with the doctrine, notice the polemics 1) “He made you in His likeness” putting all on equal footing; 2) “Jesus died to buy your soul out of hell” not indulgences, confessing to a priest, or other works; 3) “Jesus died.. with His own heart’s blood to bring you to heaven” not the monastics and certainly not the pope.

During Wycliffe’s first years at Oxford, the archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Bradwardine, of whom the student would have been acquainted, died of the Black Death (August, 1349). Bradwardine’s treatise On the Cause of God against the Pelagians greatly shaped Wycliffe’s young mind. The treatise reasserted man’s need of redeeming grace as taught by Paul and as expounded by revered Catholic theologian Augustine of Hippo.

St. Augustine had detailed Paul’s teaching in his own doctrine of Original Sin, developed in the early church struggle against Pelagianism. This teaching, later named a heresy, taught that mankind did not inherit Adam’s sin nor did mankind need God’s grace to fulfill the law. In essence, people had the ability to save themselves through good works.

In the Scriptural tradition of Paul, St. Augustine, and Archbishop Bradwardine, Wycliffe theology adhered firmly to a person’s need for divine grace. God’s grace for salvation through faith in Jesus Christ necessarily opposes works righteousness and/or the attribution of any divine capability to a human being.

Judgment on the Clergy

Though contemporary writers interpreted the Black Death as God’s judgment on sinful people, Wycliffe’s personal reflection on the desolation took on a different twist. He believed the plague did indeed have apocalyptic significance, not on sinful people however, but specifically against the clergy.

After completion of an arts degree at Merton College in 1356, he voiced these beliefs in a small treatise, titling it with apocalyptic urgency: The Last Age of the Church. This early work initiated the development of his beliefs concerning the disreputableness of the clergy and significantly the pope.

The Begging Friars

But if that initiated his concern and disdain for the corruptness of the clergy, it was firmly established in 1360 and the few years following. During this time he took on the Mendicants, especially the Franciscans and Dominicans. Though these groups had started out with a Christian fervor to serve Christ and proclaim the Gospel, they too had become quite corrupt and self-righteous.

The detailed ordeal of Wycliffe’s battle against the monastics is narrated well in the biography by Thomas Murray (cited at the end). Suffice it to say the “begging friars” were wreaking all kinds of havoc at Oxford among the school administration as well as the younger students, which extended to their parents. And all for quite grandiose and selfish reasons. After the archbishop of Armagh died in 1360, it fell upon Wycliffe to defend the school and students against these “devilish friars.” And defend, he did.

Treatise Against the Orders of the Begging Friars–in the Maternal Tongue

Sometime around 1361, he wrote “Against the Orders of the Begging Friars” and 3 other small treatises to combat these monastic groups. He denounced their practices citing Scriptural precedents one after the other. Surely the devil has not heard such sound refutation of his deceit since he tempted Christ in the desert. And to top it off, the four treatises weren’t written in Latin—which was relegated to the academe—otherwise the younger students, their parents, and importantly, the friars themselves, would not be able to read them. [note: it was only at the Second Vatican Council in 1962 that the widespread use of “maternal tongues” were allowed in the Mass instead of Latin!] Thomas Murray adds:He used also in this controversy his own maternal tongue, and not the then monastic jargon of the Latin; so that what he wrote or spoke was addressed, not to learned clerks only, but to the generality of the gentry and people of the land; and thus it came to have much more force and weight.

Oxford and secular administration lauded Wycliffe’s efforts. But then there was the pope, who for financial reasons, sided with the friars. Nonetheless, his treatises to date, which spoke by and large against the clergy and monastic orders, established a firm foundation for his political work, and more importantly for his theology.

The Intelligence of the Oxford Intellectual

Wycliffe’s keen intelligence is implicit in any discussion of his work. But let it be stated explicitly here—his intellect was far superior to his colleagues. As a young student he memorized Aristotle, but his memorization skills soon turned to the Bible. Murray says that Wycliffe’s Bible was his constant companion and that he could be seen all over campus reading it voraciously.

As an Oxford scholar, he wrote many books on theology, politics, and philosophy. These compositions required Wycliffe to undertake a thorough investigation of Scripture. Eventually, he fulfilled his doctoral requirement by giving a series of lectures commenting on the whole Bible (!).

By 1371, he was recognized as Oxford’s leading theologian and philosopher. In 1372 he received the Doctorate of Divinity.

From 1345-1372, as one author said “marked sixteen years of incessant preparation” adding “and to this point no open conflict with Rome had arisen,” open, being the operative word.

Though certainly “open” conflict with Rome did not yet exist, these formative years had paved the straight and narrow way to Wycliffe’s greatest contribution to Christian thought and history: “The supremacy of Scripture as the only reliable guide to the truth about God, and its message of God’s salvation by grace. Christians should rely on the Bible rather than on the teachings of popes and clerics.” He greatly criticized the papacy, all levels of clergy, monasticism, and many other non-scriptural doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, including indulgences and transubstantiation. As a precursor to John Wesley, he also elevated both lay spirituality and lay service in and for the church.

Timeline of Writings and Conflict With Ecclesiastical Powers

Tension and power struggles were plentiful between the monarchy and the church during this time. Conflicts also existed between France and England. All of this paints the background of Wycliffe’s life. It seems he interacted with this chaotic context, especially chaotic for someone dedicated to the truth of Scripture and a concern for souls, as if it had been a choreographed dance. That is, a divinely choreographed dance.

His thought and resolve remained consistent throughout the rest of his life. And Scripture, always held pride of place.

1370-1376

- 1370-71 recognized as the leading theologian and philosopher of the age at Oxford, thus second to none in Europe; For a brief time Oxford was considered superior to Paris in academic leadership.

- 1374: Part of a delegation sent to Bruges to negotiate disputes between the monarchy and the papacy

- 1375: On Divine Dominion expounded the government of God and the 10 commandments; attacked the temporal rule of clergy, stating instead that the king is above the pope in temporal things; he also denounced church corruption in the collection of annates and indulgences which he called simony.

- 1376: On Civil Dominion opposed the governing methods of the rule of the Church and especially the ownership of property and great wealth held by the Church, even calling for the royal divestment of all church property; argued that only the godly had the capability to exercise lordship and that the ungodly have no authority over others.

1377-1378

- 1377: (Feb) first official condemnation by Pope Gregory XI in part due to Wycliffe’s ideas on lordship and church wealth; Arguing that the Church had fallen into sin, he believed the church should give up all its property and the clergy live in complete poverty.

- 1377: summoned to appear before the Bishop of London, though the exact charges are not known. Mostly likely it was related to his opposition to clergy wealth and power. The case was appealed to Rome.

- 1377: increased attacks against Wycliffe from English clergy.

- 1377: (May) Pope Gregory XI issued a bull against Wycliffe denouncing 18 of his theses as erroneous and dangerous to the Church and State.

- 1378: Election of rival pope and the beginning of the 40-year Papal Schism. Wycliffe’s appeal to Rome was overlooked since the Papal Schism was just breaking out.

- 1378: (March) put on trial at Lamberth which was thwarted by means of the queen mother’s support.

- 1378 – The bishops were divided over Wycliffe’s teaching (some had rites of poverty) but found unity in putting him under house arrest at Oxford and censoring him from speaking out further on the issues at hand.

- 1378: *significant* returned to Oxford; not alone in attacking the corruption and abuses in the church, but the one major figure at the time to go behind the practices to attack the doctrines of contemporary Catholicism.

- 1378: De incarcerandis fedelibus (“On Putting the Faithful in Prison”) argued for the legality of the excommunicated to appeal to the king and his council against excommunication; in this treatise he laid open the entire case, in such a way that it was understood by laypeople. He wrote 33 conclusions in Latin and English. The masses, some of the nobility, and his former protector, John of Gaunt, rallied to him. Before any further steps could be taken at Rome, Gregory XI died.

- 1378: De veritate Sacrae Scripturae (“The Truth of Sacred Scripture”), expressing his fundamental belief that “Scripture proceeds from the mouth of God.” Wycliffe’s reverence for the Bible as the supreme authority for Christian life and thought is amply shown in his numerous references to it as well as in his ultimate resolve to have it translated into English and made available to the public at large.

- 1378: marks definitive break with Catholic tradition in making Scripture the final authority by which the church, tradition, councils, and even the pope must be tested. Wycliffe believed that all Christians should read the Bible for themselves, not just the clergy, and encouraged the translation of the Bible into the everyday language of the time.

- 1378: De Ecclesia (“The Church”) reaffirms and expounds the principles found in On Civil Dominion; it launched an even greater attack upon the wealth, power, and decadence of the church using the Bible as the standard. Wycliffe declared that the members of the church are God’s elect, but no one, not even the pope, can be sure of his election. All true Christians have direct personal access to God and enjoy a common priesthood. Wycliffe lays heavy stress on moral character as a mark of the true Christian. On the other hand, immorality, the lust for temporal power and wealth among the clergy is evidence that monastic orders and the papacy should be abolished. In addition to downgrading the clergy, he elevated the dignity of the true Christian layman, even stating a priest was not required to administer Holy Communion.

1379-1380

- 1379: De Protestate Papae (Concerning the Authority of the Pope), a treatise that, at its core, exalted Holy Scripture. Wycliffe was above all open and candid when it came to the church’s disregard in teaching the Bible which is the timeless “exemplar” of the Christian religion, and alone stands as the standard of doctrine, to which no church authority might legitimately add. He also stated that the papacy is an office instituted by humans not by God.

- 1380: De Eucharistia (The Eucharist) a treatise denying the Roman doctrine of transubstantiation, belief that the body of Christ is sacramentally concealed in the elements. Arguments included that 1) it is unscientific, 2) a recent innovation defined at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 and 3) contrary to Scripture. Wycliffe did not deny that Christ’s body and blood are in some sense present in the Eucharist. Here he believed himself to be following older Catholic traditions, as found in Fathers such as Ambrose and Augustine.

These last attacks on Roman Catholic teaching, including Scripture as sole authority and the denial of transubstantiation, led to Wycliffe losing favor with the government.

1381-1384

- 1381: A peasants’ revolt in England was partly blamed on Wycliffe’s teachings; one of the leaders, John Ball was alleged to be a disciple of Wycliffe. Wycliffe disowned the revolt.

- 1382: Wycliffe was finally forced to withdraw from Oxford but was not put to death.

- 1384: After suffering two strokes, Wycliffe died naturally in December.

Mail received from Wycliffe Associates! I am not affiliated with this organization in any way except to receive an occasional outreach for fund-raising. Wycliffe Global Alliance is the international “DBA” name (2011) for what is more commonly known as Wycliffe Bible Translators, one of the world’s largest international organizations dedicated to translating the Bible for every language group that needs it–named after John Wycliffe. Though declared a heretic by the Roman Catholic Church in 1415, his legacy and teachings have stood the test of time. His lasting impact on Christianity and the Church are far, far outweighs any of his adversaries.

Wycliffe’s Legacy

The Bible: The Word of God to ALL People

Wycliffe viewed the Bible as the Word of God written to every person. Therefore, he felt personally obligated to render the Scriptures in a translation that everyone could read.

Keenly aware of the mistreatments in the church, which he wrote and preached against—bribery in the monastic orders, papal taxation, the confession, church infringement in everyday life, indulgences, etc.—he knew that everyday believers were left defenseless as to divine truth. Not only did this allow clergy to take advantage of people, but on a personal basis, it damaged their understanding of Christ’s grace, their relationship with God, and Christian witness in their communities and in the world as a whole.

Three overarching points stand out in his doctrine of Holy Scripture, all of which his other teachings find authoritative standing under:

- the Bible is the ultimate norm by which the church, tradition, councils and even the pope must be tested;

- it contains all that is necessary for salvation—Christ alone—without the need of pilgrimages, works, and the Mass;

- all Christians, not just the clergy, ought to read Scripture for themselves.

For these primary reasons, Wycliffe encouraged the translation of the Bible into the everyday language of the time. This translation is now known as the Wycliffe Bible.

The Wycliffe Bible—The First English Bible

The first English Bible translations began to appear in 1380, though it is not known how closely Wycliffe himself was involved in the translations. It is known that he distributed copies of some translations, possibly containing only a few books, when he sent out the “Poor Preachers.”

Two separate versions of the Wycliffe Bible now exist, from 1384 and 1388. The 1388 version is considered to be superior. Neither of them was printed until 1850.

In the last years of his life, Wycliffe embarked on the task of translating the Latin Vulgate Bible into English. With the help of his associates, John Purvey and Nicholas of Hereford, the two complete versions of Scripture were produced. The 1384 version was an extremely literal translation, following the Latin word for word, even violating the English word order. The 1388 version more closely followed the English vernacular of the time. Because the translation was made from the Latin Vulgate text, it also included the Old Testament apocryphal and deuterocanonical books. (Catholic Bibles still include these texts today.)

Though John Wycliffe’s involvement in the translation is not known, it is his translation, rightfully bearing his name. If it had not been for his earnest and influential belief in Scripture as the Word of God to all people, and the need of people to read it for themselves, the translation would have never gotten done.

Conclusion—In Wycliffe’s Own Words

A line drawing of the death of Wycliffe. Upon his death, he had many supporters and followers called “Lollards” who carried his teachings forward.

You say it is heresy to speak of the Holy Scriptures in English. You call me a heretic because I have translated the Bible into the common tongue of the people. Do you know whom you blaspheme? Did not the Holy Ghost give the Word of God at first in the mother-tongue of the nations to whom it was addressed? Why do you speak against the Holy Ghost? You say that the Church of God is in danger from this book. How can that be? Is it not from the Bible only that we learn that God has set up such a society as a Church on the earth? Is it not the Bible that gives all her authority to the Church? Is it not from the Bible that we learn who is the Builder and Sovereign of the Church, what are the laws by which she is to be governed, and the rights and privileges of her members? Without the Bible, what charter has the Church to show for all these? It is you who place the Church in jeopardy by hiding the Divine warrant, the missive royal of her King, for the authority she wields and the faith she enjoins.

Until Next Time—

The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all. 2 Corinthians 13:14

Resources:

David B. Calhoun, ‘John Wycliffe: “The Morning Star of the Reformation”’ accessed at http://www.cslewisinstitute.org/John_Wycliffe_FullArticle

R. T. Jones “John Wyclif “ in New Dictionary of Theology eds. Sinclair B. Ferguson, David F. Wright, J. I. Packer (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1988), 733.

Anthony N. S. Lane “John Wyclif” in Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals eds. Timothy Larson, David Bebbington, Mark A. Noll (Downers Grove: Intervarsity, 2003), 753-754.

“John Wycliffe” accessed online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Wycliffe 12/27/2017.

Other Resources:

John Wycliffe, Against the Orders of the Begging Friars can be accessed at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A15298.0001.001?view=toc

A popular image with an article depicting Wycliffe who struck the spark, Hus who lit the candle, and Luther who wielded the torch can be accessed at https://www.thereformationroom.com/single-post/2017/04/23/Are-You-Passing-On-The-Torch

Thomas Murray, The Life of John Wycliffe, 1829; this is available as a free eBook on Google Books and is a nominal price for Kindle.

Tracts and Treatises of John De Wycliffe: with Selections and Translations from His Manuscripts, and Latin Works / Edited for the Wycliffe Society, with an Introductory Memoir, by Robert Vaughn; available on Google Books and can be accessed here.

The Wikipedia article lists many additional resources.