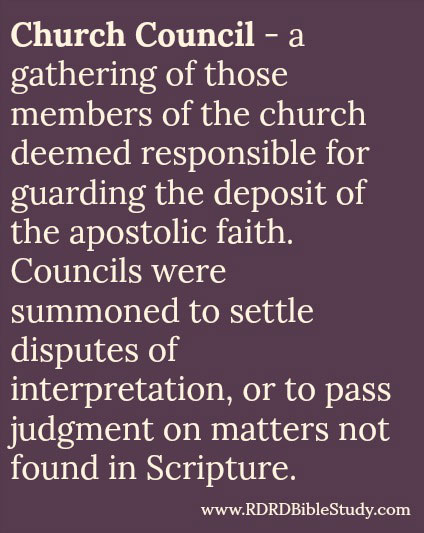

A Date to Memorize: AD 325 The Council Of Nicaea

When viewed through the lens of time, some events in Christian History emerge from such a conflation of circumstances that they are nothing short of miraculous. One such event is the Council of Nicaea, a perfectly timed orchestration of the inscrutable ways of the Lord God. Nicaea is a figurative Red Sea Crossing for Christianity—from persecution to freedom, from pilgrims without a home to citizens with a homeland.

Normally DTM feature posts are short and to the point. But this one is a little longer for two reasons:

1) multiple moving parts converging precisely at the right time to bring about this council, and

2) the resulting dynamics of a) doctrinal proclamation and b) change in the church’s relationship with the world.

The dispute to be settled at the church’s first ecumenical council—the divinity of Christ. This would certainly be no small task, as the church struggled to put into words the mysteries of God.- Two parallel developments—each comprised of multiple, yet related, events—led to this monumental meeting:

The early Church’s ongoing effort to define the nature of Christ and the character of His work. - The Emperor Constantine’s conversion and rise to power.

Defining the Nature Of Christ

In response to the central question of how to define Jesus’ special status based on NT phrases—Son of God, Word, Logos of God, and Savior who is one with the Father—early theologians proffered many answers. A complete discussion of all the answers, misunderstandings, and heresies involving the nature of Christ could fill a large library.

In general, however, pre-Nicene answers can be grouped into two categories:

- The Monarchianists—stressed the unity of the Godhead, i.e. the unity of the monarchy of God, from “monarch,” a Greek compound word meaning “one source.” Included in this category are Sabellianism or modalism, and adoptionism.

- The second category is comprised of teachings that stressed distinctions between the Father and the Son, in particular the Son’s subordination to the Father.

Subordinationism prompted one of the greatest heresies of Church history—Arianism. Its founder, Arius, admitted that the Son was with God, but didn’t believe that the Son was God. Following the trajectory of his teaching led to a division of the nature of God into three parts.

Arianism became a widespread heresy that led to much inner strife and division within the church. From 318 until the council in 325, a complex and chaotic series of meetings, letters, arguments, and debates took place to settle the controversy, but to no avail.

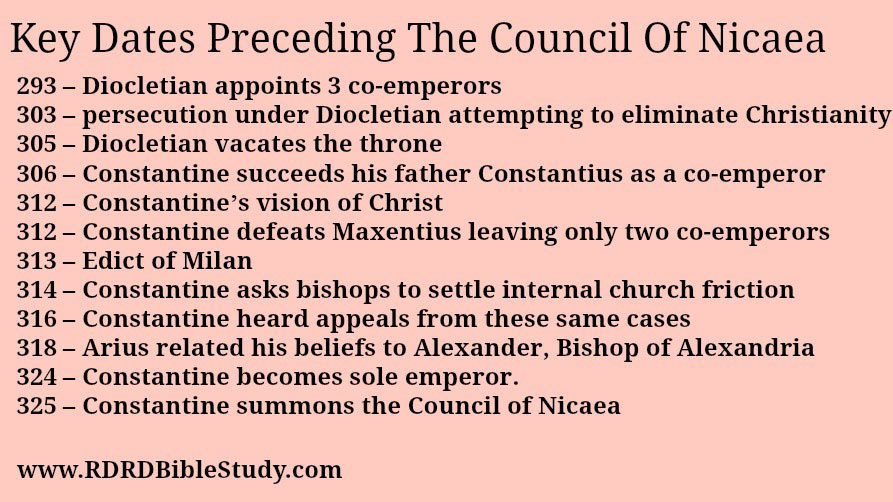

Christianity’s Years Prior To Constantine’s Advancement In The Empire

Constantine presides over church cases left over from the persecution of Diocletian. AD 314

In the years leading up to the Council, three sore points loomed large: 1) the Jews were increasingly at odds with Christians; 2) Rome did not like the church saying that only Jesus should be called Lord and not Caesar. An essential part of this being that Christians would not offer sacrifices to Caesar or the Roman gods. 3) Christians were at odds with other Christians primarily over Arianism, and secondarily over administrative issues.

Emperor Diocletian (ruled 285-305) wanted to stabilize and unify the empire. Seeing the church as divisive and disruptive, he hoped to eliminate Christianity, thus reducing religious conflict. History records that persecution under Diocletian (beginning in 303, the edict was officially rescinded in 311) was the bloodiest and most barbaric of all.

Being thus committed to the ruling philosophy of Pax Romana, “Roman Peace” and the efficient rule of the empire, Diocletian sought to establish a thorough empirical administration. He divided the realm into four districts and set co-emperors over each. The westernmost district was given to Constantius Chlorus, the father of Constantine. In 306, Constantine succeeded his father as co-emperor.

In AD 305, Diocletian vacated the throne leaving 3 co-emperors (a flurry of names as different people assumed the positions) to fight for the right to become the next emperor.

Constantine’s Conversion

The sign in Constantine’s vision – Chi Rho, the first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek. The symbol is also called a “labarum.”

In 312, Constantine saw a vision that changed his entire life, in fact the entire world. In the vision, Constantine was praying to the god of his father when “he saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and an inscription, CONQUER BY THIS attached to it… Then in his sleep the Christ of God appeared to him with the sign which he had seen in the heavens and commanded him to make a likeness of that sign which he had seen in the heavens, and to use it as a safeguard in all engagements with his enemies.”

After this vision, Constantine adopted the sign as his personal insignia, the labarum, the intertwined first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek, Chi Rho. This emblem was placed on the swords of Constantine’s army.

Constantine Becomes Emperor And An Advocate For Christianity

In AD 312 Constantine defeated Maxentius at the battle of Milvian Bridge, in an area north of Rome. Some historians say that Constantine’s victory at Milvian Bridge was more important for the history of Christianity than for the history of Rome.

After the defeat of Maxentius, two co-emperors remained—Constantine and Licinius. In 313, remarkably, Constantine arranged with Licinius to issue a decree legalizing the Christian faith and making toleration of all peaceful religions the rule throughout the empire. This momentous agreement is called The Edict of Milan.

As Constantine continued to gain power in the empire so his determination to promote the Christian faith. As early as 314 Constantine had asked several synods of bishops to settle internal church friction over questions remaining from the persecution by Diocletian—should Christians who denounced the faith in order to avoid persecution be excommunicated? Two years later he himself heard appeals from these cases.

Battle of Constantine against Maxentius. Vatican Museum, Italy; Raphael’s Room; detail C. Val. Avril; (Note the help of the angelic host.)

Constantine also grew more powerful in affairs of state, and in 324 he became Rome’s sole emperor. As far as emperors go, Constantine too sought to uphold the imperial standard of Pax Romana. As his predecessors, he too was concerned with the stability of the empire and conflict resolution caused by religious discord.

In addition to being a proponent of Christianity, the emperor felt that the Christian faith could be used to bring unity to his empire. In order for this to take place, Constantine set out to settle disputes within the church. The major point of strife centered on Arianism. But some practical questions were also causing conflict, including 1) how to set the date for Easter, and 2) how to resolve disputes between the large episcopal cities.

The Council of Nicaea – AD 325

The theological issue before the council was the divinity of Christ. Specifically the council sought a resolution to heal the schism in the church caused by the heretical teachings of Arianism.

Arius’ teachings diminished the deity of Jesus Christ. He claimed that Christ was subordinate to the Father, because Christ had been generated from the Father. This implied that Christ was both created and not eternal, though Arius held that his generation occurred before time began

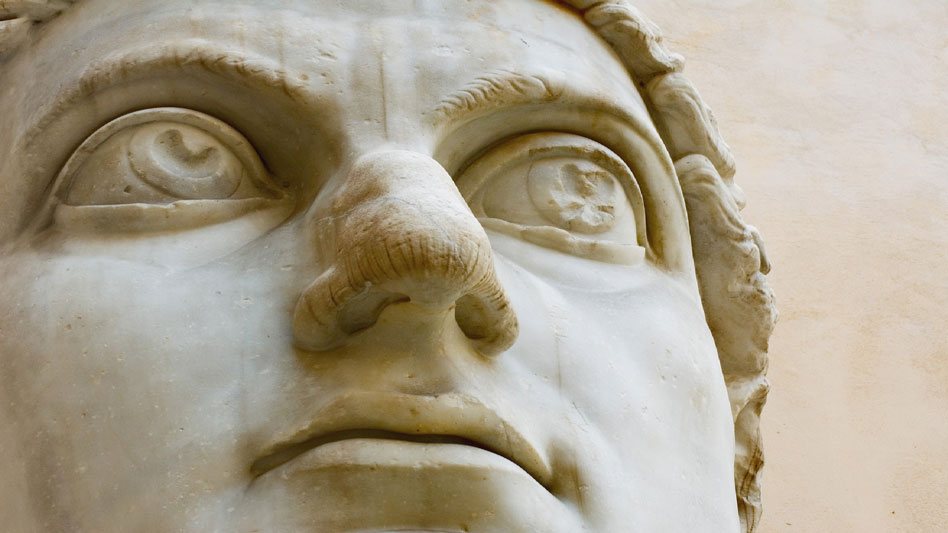

Emperor Constantine. From the colossal statue remains.

In addition to defining this crucial doctrine of Christianity, the heightened significance of the council derives from the way social and political forces brought the council together—it was convened by the Emperor Constantine.

In a letter calling for the council, Constantine explains his twofold theological and political purpose:

My design then was, first, to bring the diverse judgments found by all nations respecting the Deity to a condition, as it were, of settled uniformity [that is, to clarify doctrine for the sake of the church]; and second, to restore a healthy tone to the system of the world, then suffering under the power of grievous disease [that is, to end religious strife for the sake of the empire].

Over 300 bishops representing almost all the eastern provinces of the empire—where the heresy was chiefly centered—and a token representation from the west, attended the council. Healing the rift within the church caused by the Arian Controversy was accomplished theologically and politically by the almost unanimous production of a theological confession—The Nicene Creed.

Theological Outcome

The Nicene definition of Christ’s divine nature set the course for Christian orthodoxy that is maintained to the present day(!).

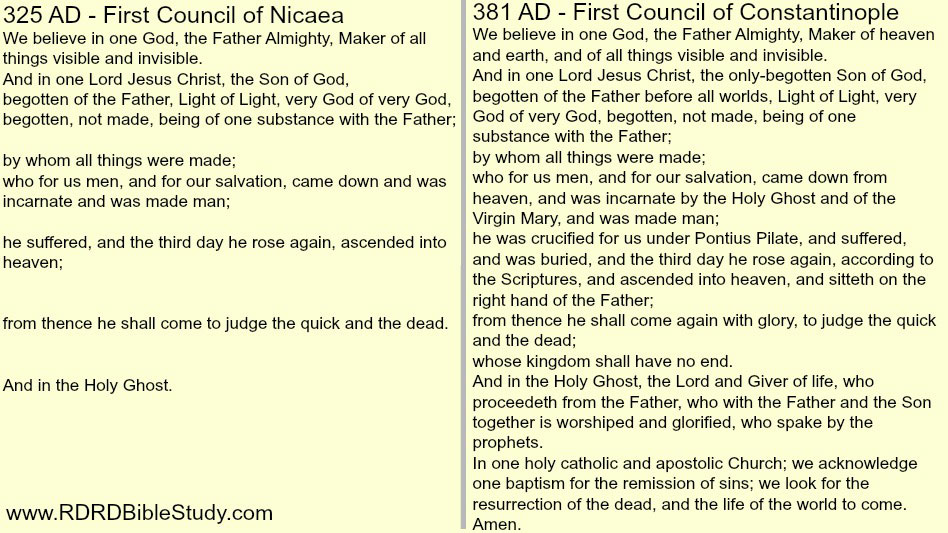

The council’s key assertions were:

1- Christ was very God of very God. Jesus Himself was God in the same sense in which the Father was God.

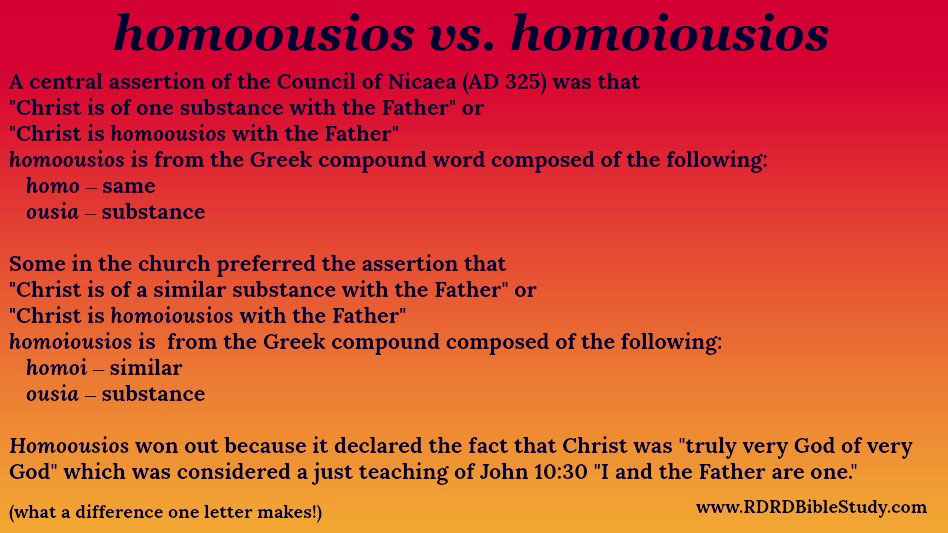

2- Christ was of one substance with the Father or homoousios, from the Greek compound word homo – same and ousia – substance.

3- Christ was begotten, not made. Never formed as all other things and persons but was from eternity the Son of God.

4- Christ became human for us men, and for our salvation

In addition, the council’s rulings on administrative and procedural matters established precedents for governance of the church.

The main propositions produced by the Council of Nicaea in 325 were reaffirmed by the bishops assembled at the 381 Council of Constantinople called by Emperor Theodosius. In the final version, known as the Nicene Creed, the section on Christ’s birth and suffering was expanded, and a fuller statement on the Holy Spirit was produced.

Political Outcome

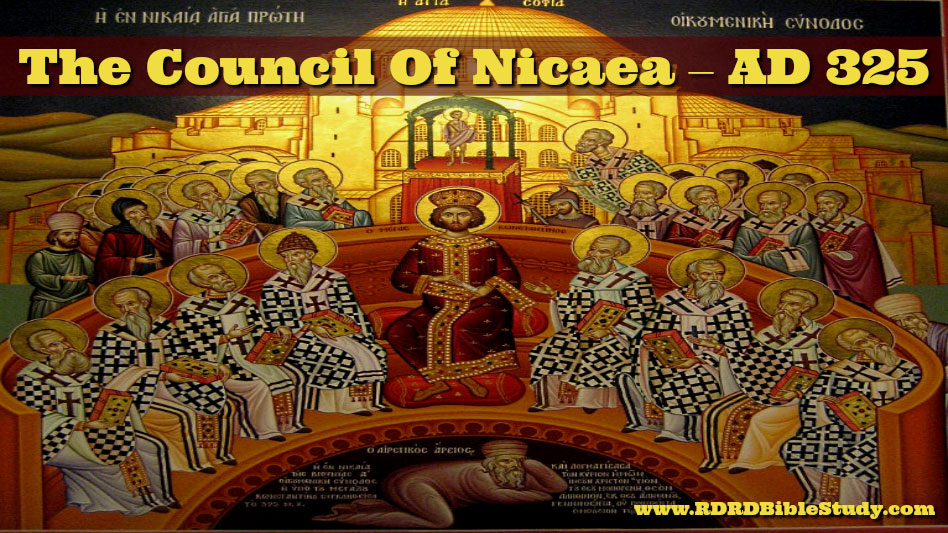

Icon depicting the Emperor Constantine and the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325) holding the Niceno–Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

Since Emperor Constantine called the council, chaired its deliberations, and undertook to implement its mandates, the church’s history turned from its course as a separate, persecuted body to the potential benefits, but also perils, of establishment, that is the state support of religion.

Church-state connections presented new situations to be worked out. For the first time ever, the Emperor was a Christian convert and the entire Roman Empire both tolerated and supported Christianity. But where would the emperors fit in relationship to the church, given the fact that they now supported the church in some way or another?

Comingling Of Politics And Theology

Though the church’s orthodox position on the divinity of Christ was settled in 325, it did not reach wide acceptance until late 4th century. Even at the time of Constantine’s death, 337, Arian diehards existed, among them Constantine’s son and successor to the throne, Constantius II.

The issue of Christ’s nature played into imperial-ecclesiastical power struggles. Arians believed the church was subordinated to the state, as Christ was subordinated to the Father. The orthodox believed the Son was equal in being to the Father, so too the kingdom of the Son (the church) was equal to the kingdom of the Father (the empire). Therefore, the authority of the bishops must be coequal to the authority of the empire.

Missorium depicting Emperor Constantine’s son Constantius II accompanied by a guardsman with the Chi-Rho depicted on his shield (at left, behind the horse). From Wikipedia “Chi Rho.”

During the time of Constantius II, Arians—both the emperor and his supporters—advocated for direct imperial control of the church. As Constantius II flexed his own power in the empire and the church, he said “Let whatsoever I will, be that esteemed a canon.” In other words, he wanted his mandates to carry the same seriousness and authority as the canons promulgated by the councils. In essence, he wanted the word of the emperor to be as the word of God. By contrast, the orthodox, or catholic party, believed the church should have autonomy over its own affairs.

As time passed, the Nicene doctrine came to be the prevalent thought in the empire thus settling some of the church-state power struggles. The affirmation of the divinity of Jesus asserted a degree of independence of the church from the state and the state from the church. So the church maintained a certain degree of autonomy.

In the 4th century, Nicene Christology declared the principle of religious liberty for prayer, worship, preaching, the use of Scripture, and the sacraments. Because the work of the Son was homoousios with the work of the Father, the life of the church had an independence that no instrument of state could transgress.

What a difference an iota makes…

Council of Nicaea Conclusion

The conversion of Constantine led to the church being recognized as a legitimate religious institution within society. As Christianity spread into northern and western Europe, the actions of rulers in initiating, promoting, supporting, and (often) dictating to the church gradually accustomed leaders in both church and state to the idea of the state support of religion, or establishment.

Mutual good came from this situation. The evangelistic mission of the church benefitted from the help of rulers. And the state benefitted when the church contributed its resources to the work of civilizing Europe’s barbarian hordes.

Mutually beneficial, yes. But what was the church giving up spiritually?

Head and other pieces of colossal statue of Roman Emperor Constantine at Capitoline Museum, Rome, Italy. Note the size of the door on the right compared to the remains.

A world where an emperor could make the critical decisions to resolve a great doctrinal crisis was a world in which the emperor’s legitimate concerns for worldly order, success, wealth, and stability almost had to become concerns as well in the church.

In this regard, Nicaea set Christianity on a course that it has only begun to abandon, and only over the past 2 or 3 centuries. The church’s calling is to the worship of God and the proclamation of the Gospel, but the Nicene course added concerns for worldly power. Ironically, the entire Nicene situation, demonstrates that God doesn’t need worldly power.

Eastern Orthodox icon depicting the First Council of Nicaea AD 325.

The distinction between church and world that Nicene Christology preserved was in fact compromised by the very events that led up to the declaration of Nicaea.

In this sense, Nicaea handed down a dual legacy –

1 acute fidelity to the great and saving truths of revelation and

2 increasing intermingling of church and world

The Nicene Creed has remained for nearly 17 centuries a secure foundation for the church’s theology, worship, and prayer(!). This foundation established the basis for later relationships between institutions of state and of church, particularly in the West.

Before

AD 96-180 – The “Good” Emperors

AD 150 – Heresies of Gnosticism and Montanism arise

AD 260 – Eusebius born

After

AD 328 – Athanasius succeeds Alexander as bishop of Alexandria

AD 337 – Constantine’s death; his son Constantius II becomes emperor

AD 354 – Augustine born; later bishop of Hippo located in North Africa

AD 381 – First Council of Constantinople called by Emperor Theodosius – reaffirmed the main tenants of the Nicene formula and slightly modified into what is known as the Nicene Creed. The Creed expanded sections on Christ’s birth and suffering and also produced a fuller statement on the Holy Spirit.

AD 451 – Council of Chalcedon

AD 530 – Benedict’s Rule

Until Next Time –

May the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all. 2 Corinthians 13:14

Homework:

- Constantine’s son, Constantius II, wanted direct imperial control of the church. He also wanted his words to be held as “canon,” that is authoritative for the church. What huge Christian organization did this eventually bring about? (HINT: It is still in existence today.)

- With the church and missions flourishing from the benefits wrought through Emperor Constantine and those leaders who followed him, why do you think Monasticism flourished only a little over a century later?